It is a curious feature of cannibalism in Africa, that it is always practiced by another group – a group that is ‘just over the hill’ – and in that place. There, it is said, one finds such a practice. I recently was talking to several Burundian friends in the nearby village about rumours of cannibalism in the Eastern Congo, just across Lake Tanganyika from us, and was assured that ‘yes; cannibalism is practiced, but only with respect to conquered enemies after a fight. It is a ritual feast, of the warriors on those they conquored – so I was told.

But who knows? Human fascination with the topic continues to abound.

Of the 19th century colonial writings that I have here in Burundi, cannibalism is mentioned in the majority of the journals. What is behind the seemingly universal fascination with the topic? One reason, was that many of the explorers were advised, by future publishers, to seek and write about findings that were bound to increase sales by way of pandering to the exotic interests of popular readers. And perhaps, for some, that was sufficient reason.

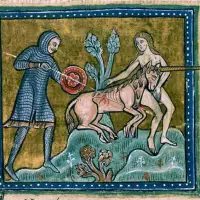

Indeed, the 19th century interest in the topic bears similarity to the medieval interest in a variety of exotic creatures that were said to inhabit unknown areas of the map. For example, the Blemmyes (whose head was in their chest) and their fantastic cohorts (no-one ever saw these creatures , either…):

Sciopod, cyclops, duplex, blemmya, cynocephalos. sebastian mc3bcnster - cosmographia c. 1559 page 1080

Here are some of the 19th century explorers’ books that take up the issue of cannibalism (though, not of the exotic creatures such as the Blemmies):

- Fetishism in West Africa : Forty Years Observation

- Great African Explorers, Kingston

- How I Found Livingstone, Stanley

- In the Wilds of Africa, Kingston

- Ismailia, Baker

- Landers Travels, Huish

- Letters from Egypt, Duff-Gordon

- Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, Livingstone

- Narrative of an Expedition to Explore the River Zaier…1818, Tukey

- Queer Things About Egypt, Sladen

- The Albert N’Yanza, Great Basin of the Nile, Baker

- The Cruise of the Snark

- The Discovery of the Source of the Nile, Speke

- The heart of Africa: Three years’ travels and adventures in the unexplored regions of Central Africa from 1868 to 1871, Volume 2 George August Schweinfurth

- The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah

- The Last Journals of David Livingstone V.1, Livingstone

- The Last Journals of David Livingstone V.2, Livingstone

- The Life and Travels of Mungo Park

-

Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa:Being a journal of an expedition undertaken under the auspices of H. B. Majesty’s government, Volume 2, Barth

- Travels in Morocco, V.1, Richardson

- Travels in the Great Desert of Sahara, Richardson

- Travels in the Interior of Africa V.1, Park

- Travels in the Interior of Africa V.2, Park

- Travels in West Africa, Kingsley

- Two Trips to Gorilla Land and the Cataracts V.1, Burton

- Two Trips to Gorilla Land and the Cataracts V.2, Burton

- What Led to the Discovery of the Source of the Nile, Speke

Sir Burton’s writings on Africa contain some of the worst racist remarks to be found in the colonial literature. That he was so widely respected and read, only served to imprint his remarks as reality on the European mind and helped to secure the colonial and imperial notion that Africans ‘needed’ Europeans in order to ‘become civilized’ and to ‘develop’ – a notion that has continued to inform development theory and practice as well as research in agriculture, livestock, and other areas unto now.

Cannibalism – or ‘anthropophagy’, as Sir Richard Burton (discussed below) termed it – was a topic that fascinated 19th Century explorers in Africa, just as it continues to peak the imagination today…

Sir Richard Burton systematically asked about possible ‘cannibal tribes’ known to those whom he visited throughout his travels in Africa. In West Africa, the Fan were said to have been cannibals, and it was in search of this practice that Sir Richard Burton set out to visit the Fan in c.1863. The visit turned into a study of cannibalism in Africa, and below are excerpts from Sir Burton’s findings.

- Richard Burton was not a particularly sympathetic writer

I made careful inquiry about anthropophagy [Cannibalism] amongst the Fan, and my account must differ greatly from that of M. du Chaillu. The reader, however, will remember that Mayyan is held by a comparatively civilized race, who have probably learned to conceal a custom so distasteful to all their neighbours, white and black; in the remoter districts cannibalism may yet assume far more hideous proportions.

Since the Fan have encouraged traders to settle amongst them, the interest as well as the terrors of the Coast tribes, who would deter foreigners from direct dealings, has added new horrors to the tale; and yet nothing can exceed the reports of older travellers.

During my peregrinations I did not see a single [human] skull. The chiefs, stretched at full length, and wrapped in mats, are buried secretly, the object being to prevent some strong Fetish medicine being made by enemies from various parts of the body. In some villages the head men of the same tribe are interred near one another; the commonalty are put singly and decently under ground, and only the slave (Maka) is thrown as usual into the bush.

Mr. Tippet, who had lived three years with this people, knew only three cases of cannibalism; and the Rev. Mr. Walker agreed with other excellent authorities, that it is a rare incident even in the wildest parts–perhaps opportunity only is wanted. As will appear from the Fan’s bill of fare, anthropophagy can hardly be caused by necessity, and the way in which it is conducted shows that it is a quasi-religious rite practised upon foes slain in battle, evidently an equivalent of human sacrifice.

If the whole body cannot be carried off, a limb or two is removed for the purpose of a roast. The corpse is carried to a hut built expressly on the outskirts of the settlement; it is eaten secretly by the warriors, women and children not being allowed to be present, or even to look upon man’s flesh; and the cooking pots used for the banquet must all be broken.

A joint of “black brother” is never seen in the villages: “smoked human flesh” does not hang from the rafters, and the leather knife-sheaths are of wild cow; tanned man’s skin suggests only the tannerie de Meudon, an advanced “institution.”

Yet Dr. Schweinfurth’s valuable travels on the Western Nile prove that public anthropophagy can co-exist with a considerable amount of comfort and, so to speak, civilization–witness the Nyam-Nyam and Mombattu (Mimbuttoo).

The sick and the dead are uneaten by the Fan, and the people shouted with laughter when I asked a certain question. The “unnatural” practice, which, by the by, has at different ages extended over the whole world, now continues to be most prevalent in places where, as in New Zealand, animal food is wanting; and everywhere pork readily takes the place of “long pig.”

The damp and depressing atmosphere of equatorial Africa renders the stimulus of flesh diet necessary. The Isangu, or Ingwanba, the craving felt after a short abstinence from animal food, does not spare the white traveller more than it does his dark guides; and, though the moral courage of the former may resist the “gastronomic practice” of breaking fast upon a fat young slave, one does not expect so much from the untutored appetite of the noble savage.

On the eastern parts of the continent there are two cannibal tribes, the Wadoe and the Wabembe; and it is curious to find the former occupying the position assigned by Ptolemy (iv. 8) to his anthropophagi of the Barbaricus Sinus: according to their own account, however, the practice is modern.

When weakened by the attacks of their Wakamba neighbours, they began to roast and eat slices from the bodies of the slain in presence of the foe. The latter, as often happens amongst barbarians, and even amongst civilized men, could dare to die, but were unable to face the horrors of becoming food after death: the great Cortez knew this feeling when he made his soldiers pretend anthropophagy.

Many of the Wadoe negroids are tall, well made, and light complexioned, though inhabiting the low and humid coast regions– a proof, if any were wanted, that there is nothing unwholesome in man’s flesh. Some of our old accounts of shipwrecked seamen, driven to the dire necessity of eating one another, insinuate that the impious food causes raging insanity.

The Wabembe tribe, occupying a strip of land on the western shore of the Tanganyika Lake, are “Menschenfresser,” as they were rightly called by the authors of the “Mombas Mission Map.” These miserables have abandoned to wild growth a most prolific soil; too lazy and unenergetic to hunt or to fish, they devour all manner of carrion, grubs, insects, and even the corpses of their deceased friends.

The Midgan, or slave-caste of the semi-Semitic Somal, are sometimes reduced to the same extremity; but they are ever held, like the Wendigo, or man-eaters, amongst the North American Indians, impure and detestable. On the other hand, the Tupi- Guaranis of the Brazil, a country abounding in game, fish, wild fruits, and vegetables, ate one another with a surprising relish.

This subject is too extensive even to be outlined here: the reader is referred to the translation of Hans Stade: old travellers attribute the cannibalism of the Brazilian races to “gulosity” rather than superstition; moreover, these barbarians had certain abominable practices, supposed to be known only to the most advanced races.

Anthropophagy without apparent cause was not unknown in Southern Africa. Mr. Layland found a tribe of “cave cannibals” amongst the mountains beyond Thaba Bosigo in the Trans-Gariep Country.He remarks with some surprise, “Horrible as all this may appear, there might be some excuse made for savages, driven by famine to extreme hunger, for capturing and devouring their enemies. But with these people it was totally different, for they were inhabiting a fine agricultural tract of country, which also abounded in game. Notwithstanding this, they were not contented with hunting and feeding upon their enemies, but preyed much upon each other also, for many of their captures were made from amongst the people of their own tribe, and, even worse than this, in times of scarcity, many of their own wives and children became the victims of this horrible practice.”

Anthropophagy, either as a necessity, a sentiment, or a superstition, is known to sundry, though by no means to all, the tribes dwelling between the Nun (Niger) and the Congo rivers; how much farther south it extends I cannot at present say. On the Lower Niger, and its branch the Brass River, the people hardly take the trouble to conceal it.

On the Bonny and New Calabar, perhaps the most advanced of the so-called Oil Rivers, cannibalism, based upon a desire of revenge, and perhaps, its sentimental side, the object of imbibing the valour of an enemy slain in battle, has caused many scandals of late years.

The practice, on the other hand, is execrated by the Efiks of Old Calabar, who punish any attempts of the kind with extreme severity. During 1862 the slaves of Creek-town attempted it, and were killed. At Duke-town an Ibo woman also cut up a man, sun- dried the flesh, and sold it for monkey’s meat–she took sanctuary at the mission house. Yet it is in full vigour amongst their Ibo neighbours to the north-west, and the Duallas of the Camarones River also number it amongst their “country customs.” The Mpongwe, as has been said, will not eat a chimpanzee; the Fan devour their dead enemies.

The Fan character has its ferocious side, or it would not be African: prisoners are tortured with all the horrible barbarity of that human wild beast which is happily being extirpated, the North American Indian; and children may be seen greedily licking the blood from the ground.

It is a curious ethnological study, this peculiar development of destructiveness in the African brain. Cruelty seems to be with him a necessary of life, and all his highest enjoyments are connected with causing pain and inflicting death. His religious rites–a strong contrast to those of the modern Hindoo–are ever causelessly bloody. Take as an instance, the Efik race, or people of Old Calabar, some 6,000 wretched remnants of a once-powerful tribe. For 200 years they have had intercourse with Europeans, who, though slavers, would certainly neither enjoy nor encourage these profitless horrors; yet no savages show more brutality in torture, more frenzied delight in bloodshed, than they do.

A few of their pleasant practices are– The administration of Esere, or poison-bean; “Egbo floggings” of the utmost severity, equalling the knout; Substitution of an innocent pauper for a rich criminal; Infanticide of twins; and Vivisepulture. And it must be remembered that this tribe has had the benefit of a resident mission for the last generation. I can hardly believe this abnormal cruelty to be the mere result of uncivilization; it appears to me the effect of an arrested development, which leaves to the man all the ferocity of the carnivor, the unreflecting cruelty of the child. The dietary of these “wild men of the woods” would astonish the starveling sons of civilization.

From Richard Burton – Two Trips to Gorilla Land and the Cataracts of the Congo Volume 1, 1876 –

Earlier than Burton, James Hingston Tuckey set out to explore the Congo in 1816 and had this to say of tribes in the delta of the Congo River, and cannibalism in general:

Extrait de l'atlas de jean-baptiste douville, 1831 voyage au congo...

This place is no doubt the St. Salva dor of the Portuguese. These chiefs have improperly been called kings : their territories, it would seem, are small in extent, the present expedition having passed at least six of them in the line of the river; the last is that of Inga, be yond which are what they call bush-men, or those dreadful cannibals whom Andrew Battel, Lopez, Merolla, and others, have denominated Jiigas, or Giagas, who consider human flesh as the most delicious food, and goblets of warm blood as the most exquisite beverage a calumny, which there is every reason to believe has not the smallest foundation in fact.

From the character and disposition of the native African, it may fairly be doubted whether, throughout the whole of this great continent, a negro cannibal has any existence…

…it is probable, that the many idle stories repeated by the Capuchin and other missionaries to Congo, of the Giagas and Anzicas, their immediate neighbours, delighting in human flesh, may have had no other foundation than their fears worked upon by the stories of the neighbouring tribes, who always take care to represent one another in a bad hght, and usually fix upon cannibalism as the worst…

Source: James Tukey, Narrative of an Expedition to Explore the River Zaier…1818

Os Filhos de Pindorama. Cannibalism in Brazil in 1557 as described by Hans Staden (b. around 1525). Stories of cannibalism in South America 'vied' with similar stories from Africa.

Related articles

- Cuisines and Crops of Africa – The Lotus Eaters of Central Africa (dianabuja.wordpress.com)

- Cuisines and Crops of Africa, 19th Century – Zambezi River Watershed in Southern Africa (dianabuja.wordpress.com)

- Cuisines and Crops of Africa, 19th Century – The Limits of Pastoralism as a Lifestyle (dianabuja.wordpress.com)

- Fasting and Feasting in Africa – Reasoned Responses to Radical Changes in Climate and Crops (dianabuja.wordpress.com)

Good post. Robert Brightman did a nice piece on the Windigo several years ago in the Ethnohistory journal.

LikeLike

Thanks – and also many thanks for sending the article; I have no OA here… Have downloaded and will read this PM. Nice to find someone ‘doing’ kinship, which seems to have gone a bit out of mainstream. At Berkeley, I can remember plowing through a variety of kin and kin-related pieces in seminars with Nelson Graburn, and finding our work quite interesting. Interesting, too, your recent entry on the dimension of ‘father’ in the new testament.

LikeLike

Pingback: Teeth-filing as a Mark of Beauty and Belonging in 19th Century Africa « Dianabuja's Blog

Pingback: Colonial Cuisine in Africa and What Followed « Dianabuja's Blog

Thanks for an interesting post. Yes, it’s always the “other” who are evil. By the way, Burton gets scorched in Tim Jeal’s new book about explorers of the Nile.

LikeLike

Thanks to you, Steve – and i’m enjoying your blogs about Barth. His observations during his journies in Sudan and also in the Middle East, are some of the best. Sorry I can’t get Jeal’s book! Glad that he sees Burton as the humbug he is…

LikeLike