Red and yellow beans for sale in a rural market stall

Dry beans are the most important food in Burundi. Being Burundian is associated with beans – their growing, processing, sales and eating. Consumption of beans cuts across all socioeconomic and ethnic lines in the country; they are a truly unifying, gastronomic force.

Beans are neither a poor people’s’ food nor a dish only for the rich: nor are they associated either with Hutu or Tutsi ‘ethnic’ groups – or with Batwa pygmies. And so today I’m going to talk about the social life of beans – Burundi style.

But preparing beans does not begin in the kitchen – or even the market – but in the field. As a matter of fact, the entire production process constitutes a series of important social interactions in which both family and friends and sometimes day laborers will participate.

Thus, it is not just sharing a meal that is social – it is the entire productive process. And the final act of sharing that meal is really ‘just’ a means of preparing to continue this annual process. Every farming family will try to grow at least a small plot of beans. In fact, a few weeks ago I was interested to see that a local laborer had planted a very small plot of beans and maize next to our compound, on unoccupied land.

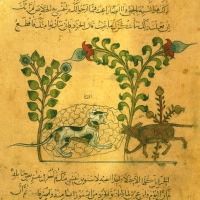

Beans were introduced to sub-Saharan Africa by Portuguese traders and colonizers from Central American – the precise mechanisms are not worked out, but it is to be supposed that – as bananas, maize, amaranth, squash, and some other crops – these were brought into ports along both east and west Africa during the colonial era by different Portuguese merchants and settlers.

Thereafter, over several hundred years, beans and other crops introduced from the Americas were adopted and adapted by local populations to specific agro-ecological and socio-economic conditions, as the crops spread to areas inland.

As a result of this diffusion, there are many varieties of beans throughout Africa; in Burundi this includes: red, white, multi-colored, ‘black’, etc. As well, different varieties have been developed by smallholders to thrive in specific ecosystems. For example, a delicious variety of yellow bean grows best in a certain semi-arid locale of eastern Burundi.

More information on the ‘common bean’ and its introduction to Africa can be found here: Background information on Common Beans

A mixture of bean varieties

Before beginning, I do want to apologize for the quality of the photos – some are digitized from my old Minolta camera pictures, and the quality is just not terribly good… blurry and off-color. That remark holds true for all of the photos used in the blog entries, in which photos are generally used to illustrate a process or an event – not necessarily to be a ‘work of art’!

As well, I would like to thank Susan Park and Farid Zadi for the opportunity of first presenting some of these materials on the Book of Rai Forum which – sadly – is no more! Thus, I share and expand here.

* * * * *

Back to Beans: To begin with, plots must be prepared, and this is nearly always a shared task. And in Burundi as in most of Sub-Saharan Africa, we’re talking about hoe agriculture. You will see that moms carry their babies on their backs as they are hoeing:

A women’s group breaking fallow ground for beans.

Men & women in the nearby village helping one another to prepare plots

Fertilizer is not used. Being nitrogen high, beans generally do not need additional nutrition. Crop rotation, intercropping, and fallow are the methods of maintaining fertility. In any case, the majority of people do not have chemical fertilizer to use except on coffee and tea (commercial) crops.

There are both ground and climbing bean varieties; beans are, to the extent possible, intercropped with another species in order to take advantage of their nitrogen; here, ground covering beans are being grown under bananas, which are a useful upperstory, diffusing sun:

Banana groves provide excellent, filtered light for ground cover beans

Climbing beans are nearly always intercropped with maize, because not only does the maize take advantage of nitrogen released by the beans – but the stocks are then used as poles up which the beans climb; a nice symbiotic relationship:

Once corn is mature, climbing beans utilize the stocks for support while supplying nitrogen that corn production requires

Where are the beans grown in a homestead? In Burundi, the ideal rugo – or homestead – is spread down a hill from top to bottom, taking advantage of the different micro-ecosystems along the slope in order to grow different crops, and with a bit of terracing on which are generally grown fodder grasses or fodder trees.

Below is depicted a homestead with a variety of crops including a small plot in the front that has a young field of intercropped maize and beans. In back, are small groves of beer and sweet bananas and on the terraces are being grown tripsacum grass for the livestock. Burundi is extremely highly populated and thus every square meter is used to greatest advantage.

A series of rugo organized along a hill. Not all of Burundi is this picturesque; this is in Mugamba Provence, south-west Burundi, where some of the finest of traditional rugo constructions are still maintained.

An idealized rendering of how the rugo – or homestead – should be organized. Burundi is a country of hills and so the majority of farms span several micro-ecosystems along a slope, as depicted and explained in the following transcect. Source: FAO

Transect of the farm of one of the families we worked with in a livestock-agriculture project , showing the major micro-ecosystems on the farm as it descends down a hill, and features of each. Interesting to note that this farmer grows yams, which is the furthest east of yam cultivation in Burundi of which I am aware (this is in central Gitega Prov.).

Once ripe, the bean stocks are collected – a joint task that both men and women share – as well as kids (although in this picture it is only women). They will be spread out in the sun to dry a bit, after collection:

Ripe beans are collected and bundled away for drying – head transport is the norm in rural Burundi. Tripsacum grasses are growing in the background, to be used in zero-grazing of cattle and goats.

Once dry, the beans are carried home, still attached to their stocks which are bundled tightly for transport. At the homes, they will be further dried, as necessary, and processed. The stocks are modestly high in protein and will be stored or sold – they are an important source of animal fodder during the dry season:

Women transporting dried beans

Then, the arduous task of ‘beating the beans’ begins – and is often done by men – it is a way of sorting the beans out from the stocks; some of the beans can be seen at the front of the pile. ( I cannot find my picture for this, and will keep looking!)

Thereafter, the stocks are carefully picked through to collect any remaining ‘stray’ beans , which you can see in the two plastic containers. Chickens are always a great help:

Cleaning bean stocks that have been picked over and beaten for the last bean. This can be a shared task, as here, where the owner (left) will give the other two a portion of the beans as payment for helping with this task.

So now, with the help of family and friends along the production process, you have your beans. Some you will keep for consumption and planting over the coming year, but some you will sell to merchants or in the market, to gain a little cash. If you’re harvest is not so good, then you’ll have to dip into your capital and buy beans at the local market, as this women is doing – a bean container is on her head:

Woman purchasing a few kgs. of beans for use in planting.

There is also a large selection of beans in the central market in Bujumbura (as well as in smaller markets), where locally grown rice can also be purchased:

Central market of Bujumbura – beans and rice of different quality

Now the only thing left to do is to cook them and eat, so that you’ll be ready to go out and grow more !

And we’ll do that in a later post….. Here:

Revised version – originally published Aug 13, 2009.Related articles

- Batwa Pots in Burundi: Traditional Clay Pot Cuisine, Pt. 2 of 2 (dianabuja.wordpress.com)

- Batwa Pots in Burundi: Traditional Clay Pot Cuisine, Pt. 1 of 2 (dianabuja.wordpress.com)

Thanks for sharing! Is there any advice you would like to share with Someone whose interested on exporting Burundis bean to near by country( RDC) for business purposes? Please let me know. Thanks!

LikeLike

Great thanks for the information which was extremely useful for a science project though i would suggest if you could write more about other fruits, vegetables and special plants if possible?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you found the blog useful! FOR other blogs on crops, see the following:

https://dianabuja.wordpress.com/category/cuisine/

https://dianabuja.wordpress.com/category/food/

Let me know if i can help you further!

LikeLike

Pingback: The Social Life of Beans in Burundi – Part 2 | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, The Middle East, Agriculture, History and Culture

Diana thanks for the insight about beans.I’m a Kenyan interested with the white beans grown in Burundi.I’ll appreciate your prompt response.Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Wild Coffee and other Indigenous Species in Central Africa | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, the Middle East, Agriculture, History & Culture

Pingback: The Social Life of Beans in Burundi – Part 2 | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, the Middle East, Agriculture, History & Culture

Pingback: Banana Beer and other Fermented Foods in Africa | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, the Middle East, Agriculture, History & Culture

Beans have often been the protein provider of choice because of its versatility and portability across borders. Culturally interwoven with stable and settle societies it has maintain a long history of cultivation.

James Lane

LikeLike

Yes indeed, James – puts to paid current notions of ‘value chains’ of crops, as being associated only with the crop.

LikeLike

Pingback: Nibbles: Guatemala, Burundi, Bees, LANSA, Moringa, Sorghum domestication

Please, just i am intersted with this litterature on beans. So i would like to get the author, town and the house of publication of this paper.

LikeLike

Hello Ndayiziga – I am the author, and the information is based on my research here in Burundi and elsewhere in Africa. Any questions, I will be happy to try to answer. Thank you for your interest!

LikeLike

I need to know the really author

LikeLike

Pingback: Republic of Burundi «

Pingback: Cuisine and Crops in Tropical Africa – Colonial and Contemporary – Pt. 2 « Dianabuja's Blog

Pingback: The Social Life of Beans in Burundi | burundi today

Maria – the role of beans as a protein supplement, once introduced into the Mediterranean and Africa, was significant. See the Rockefeller article to which I give a link, on some of the nutritional aspects that you mention.

LikeLike

lots of food for thought in this post, diana

beans have always been an important part of the mediterranean diet, due to their high nutritional content – they were the main source of protein in crete for many years until meat became easier to produce, store and acquire

LikeLike

Cynthia – Thanks. Your question is important; it is thought that beans – as a number of other crops – were introduced by the Portuguese during their trade and colonization of sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, think I’ll edit my entry to reflect this. Thanks for the thought.

LikeLike

Wonderful post, Diana! Any information about how beans came to be so important in the diet? In Haiti, beans, generally small red ones, dominate the cuisine.

LikeLike