Mungo Park routinely describes foods and crops – as well as cooking and serving methods – throughout his extensive travels in west Africa. His are amongst the most detailed sources on these topics for the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In this entry, he provides information on the use of wild varieties of bamboo and mimosa as hunger crops as well as for medicine, building and crafts. This is followed by further information on bamboo and mimosa and their multipurpose uses.

- circa 1820: Engraving of the African explorer, Mungo Park (1771 – 1806), by W T Fry. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

A little before it was dark, having crossed the ridge of hills to the westward of the river Boki, we came to a well called Cullong Qui (White Sand Well), and here we rested for the night.

We departed from the well early in the morning, and walked on with the greatest alacrity, in hopes of reaching a town before night. The road during the forenoon led through extensive thickets of dry bamboos. About two o’clock we came to a stream called Nunkolo, where we were each of us regaled with a handful of meal, which, according to a superstitious custom, was not to be eaten until it was first moistened with water from this stream.

About four o’clock we reached Sooseeta, a small Jallonka village, situated in the district of Kullo, which comprehends all that tract of country lying along the banks of the Black River, or main branch of the Senegal. These were the first human habitations we had seen since we left the village to the westward of Kinytakooro, having travelled in the course of the last five days upwards of one hundred miles.

Here, after a great deal of entreaty, we were provided with huts to sleep in, but the master of the village plainly told us that he could not give us any provisions, as there had lately been a great scarcity in this part of the country. He assured us that, before they had gathered in their present crops, the whole inhabitants of Kullo had been for twenty-nine days without tasting corn [grain – not maize], during which time they supported themselves entirely upon the yellow powder which is found in the pods of the nitta [Parkia biglobosa], so called by the natives, a species of mimosa, and upon the seeds of the bamboo-cane [Oxytenanthera abyssinica,], which, when properly pounded and dressed, taste very much like rice.

As our dry provisions were not yet exhausted, a considerable quantity of kouskous was dressed for supper, and many of the villagers were invited to take part of the repast; but they made a very bad return for this kindness, for in the night they seized upon one of the schoolmaster’s boys, who had fallen asleep under the bentang tree, and carried him away.

The boy fortunately awoke before he was far from the village, and, setting up a loud scream, the man who carried him put his hand upon his mouth and ran with him into the woods; but afterwards understanding that he belonged to the schoolmaster, whose place of residence is only three days’ journey distant, he thought, I suppose, that he could not retain him as a slave without the schoolmaster’s knowledge, and therefore stripped off the boy’s clothes and permitted him to return.

Source: Mungo Park – Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa in the years 1795, 1796, 1797 – Volume 2. London 1816.

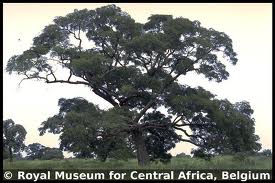

The following information on the nitta tree explains the varied uses of different parts of the tree, and suggests ways to encourage its continued propagation.

Parkia biglobosa

[Synonyms : Inga biglobosa, Inga senegalensis, Mimosa biglobosa, Parkia africana, Parkia clappertoniana, Parkia oliveri, Parkia roxburghii]AFRICAN LOCUST is a tree. Native to tropical western Africa it has small, red or orange flowers, followed by fruit pods.

It is also known as African locust bean, Arbre à farine (French), Clapperton’s parkia, Dadawa (Hausa), Dawa dawa (Hausa), Farroba (Portuguese), Kedaung (Indonesian), Locust bean tree, Mimosa pourpre (French), Néré (French), Nittabaum (German), Nitta nut, Nutta nut, Qiu hua dou (Chinese), and West African locust bean.

The flower heads last one night. Together with bees, the bats are the prime pollinators of the flowers – the flowers are rich in nectar and bats visit the tree at night to sip this. The seeds are dispersed by birds and mammals.

The tree is considered to be threatened in the wild.

The value of African locust’s fruit to the local community is strikingly illustrated by reports that indicate how farmers cultivating sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) in some remote areas still allow this tree (and shea, Vitellaria paradoxa) to grow among their crops even though their sorghum yield is likely to be drastically reduced (70% by the former and 50% by the latter).The sweet-tasting, yellow fruit flesh is used to make drinks and the roasted seeds are ground for a coffee sometimes referred to as café du Sudan. In addition to the edible flesh from the long and narrow, blackish-brown fruit pods (said to be a particular delicacy in children’s eyes), the hard seeds are processed to produce a powder or paste that are an important source of protein and known widely as ‘Soumbala’.

The preparation of soumbala can be quite complicated and time-consuming and as it has a fairly short shelf-life the procedures involved have become woven into everyday life in many communities in the western African region. After the seeds have been repeatedly boiled they are husked. Then (often mixed with wood ash to reduce the smell) they are left to ferment for several days in leaf-lined baskets.

Once fermented they are partially dried, or they are pounded to a cheesy paste and formed into balls or pyramids that are stored for later use. Soumbala in ultimate dried seed form is used as a condiment or garnish – and as a paste it offers a nutritious flavouring for soups, stews and sweetmeats.

Apart from dietary and traditional practices there are also economic considerations for the families in these communities as the production of soumbala could be viewed effectively as a cottage industry. Many of the women regularly made soumbala in their own homes, not just for their own use but also as a source of income as they sold it in the local markets.

Today the diet, associated traditional practices and economic benefits may well be under threat. Foreign commercial flavourings are being aggressively promoted by Western international food processing conglomerates. Authorities report that these foreign flavourings have lower calories and dietary protein but perceived advantages of a far longer shelf-life and ready-made ease of preparation and have begun to infiltrate the region supported by intensive and often aggressive advertising campaigns.

Aware of this, local research with subsequent guidance has encouraged at least one local entrepreneur to begin commercial production of soumbala. If this enterprise expands it will mean that the diet in the region will not be impoverished to the same extent as could be predicted from the use of imported products – even though soumbala’s local commercial production would still have a significant impact eventually on traditional practices and incomes in individual homes.

The thick, reddish-brown bark has been used for tanning and staining leather red. It has also provided a dye. Some authorities have noted that the fruit have been used as a mordant in indigo dyeing.

Today still some traditional potters in tropical western Africa make a diluted gum solution from the fruit pods. This is used to seal the pots and produces the mottled surface on them for which they are especially singled out.

Local fshermen have thrown fruit pod shells into the water to stun fish.

It is reported that in the dry season farmers have broken off branches from surrounding growth in order to make it easier for livestock to get at the tree’s young leaves, shoots and fruit pods. The dried seeds have also offered animal fodder.

Locusts are known to gorge on the fruit pods and strip the trees bare.

The very hard, reddish-brown wood has been used locally for general carpentry and is said to be sought after for carving. It yields a high quality charcoal and has also been burnt as fuel.

Medicinally, the seeds have been used in local treatments for stomach upsets – and in The Gambia the bark has been used for easing toothache.

With the leaves and fruit pulp as well, some authorities note that the various parts of the tree account for treatments for at least 40 different ailments in African medicine apart from those already mentioned, including dysentery, intestinal disorders, bronchitis, asthma, ulcers, rickets, sore throat and dermatitis.

Source: Parkia biglobosa © Sue Eland 1991

Picture sources: Royal Museum for Central Africa – Belgium

The bamboo species mentioned by Park is Oxytenanthera abyssinica, which is found across the southern Sahel from Senegal in the east to Eritrea in the West. It is an extremely hardy bamboo, which in many areas is being cut back such that regrowth is threatened.

Oxytenanthera abyssinica is one of the few indigenous bamboos in tropical Africa. It usually forms dense clumps consisting of many stems, which are 5–10(–15) m tall and 3–8(–10) cm in diameter. It is distributed throughout tropical Africa outside the humid forest zone, from Senegal east to Eritrea, and south to Angola, Mozambique and northern South Africa, mainly at 300–1500 m altitude. It is often planted.

The stems are widely used for construction, fencing, furniture and fish-traps, and they are also used for stakes, trellises, tool handles, household implements and arrow shafts. The use of dry stems as fuel is widespread and they are sometimes made into charcoal. Split stems are used for basketry. Sap from the plant is collected for wine making in Tanzania and Malawi, the fresh or dried leaves are used as fodder, and the seeds and young shoots as famine food. Oxytenanthera abyssinica is useful in shelterbelts and windbreaks, for erosion control and as an ornamental plant. The rootstocks and leaves are used in traditional medicine.

Source: Oxytenanthera abyssinica

Oxytenanthera abyssinica stands in eastern Burundi, which are going to seed. I took this picture a few years ago, before these and other stands had been totally removed by entrepreneurs from Bujumbura and elsewhere, wanting to put in fast-growing food crops for sale.

Fruiting oxtenanthera aby. This species of bamboo goes to seed only every seven years, and then dies back, as seen in the above picture. Source: Kew Gardens

Seeds from Oxytenanthera abyssinica have been collected in west Africa by the Millennium Seed Bank Project’s partner institution in Mali, the Institut d’Économie Rurale. It is a priority for conservation because it is a very useful plant, its natural habitat is under increasing threat, and it sets seed only once every seven or so years. The bamboo has many uses and is therefore highly valuable to local people, but is threatened in the wild by over-harvesting, animal grazing and urban development, as well as bush fire. It is now a fully protected species in Mali; harvesting is carefully controlled and reintroduction programmes have been established.

Source: Kew Royal Botanical Gardens

The following blog describes the use of bamboo in the construction of floating bridges: Mungo Park Discovers a Toll Bridge made of Bamboo in the Western Sahel, 1797

These wild species are multipurpose and are generally protected by farmers in their fields or in common-lands. However, past decades of agronomic research and extension have focused on food crops, neglecting the importance of these multipurpose plants. Happily, however, this is now changing and national agriculture research institutes of several countries in sub-Saharan Africa are giving more attention to them, often with the assistance of ICRAF (International Agroforestry Centre, Kenya).

Pingback: Find Me A Cure

Pingback: Kurchi (Holarrhena pubescence) | Find Me A Cure

Pingback: The Adventures of Mary Gaunt, Alone in West Africa in 1910 | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, the Middle East, Agriculture, History & Culture

Really good!

A funny coincidence: in the archive I am working upon at the University of Bergen, it was yesterday that I came upon an article from the “Proceedings of a Seminar held on the occasion of the Mungo-Park Bi-Centenary Celebration at the Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh, 3rd and 4th December 1971”.

Thanks!

LikeLike

What a funny coincidence! Would love to see those Proceedings! Glad that you enjoyed the entry; Mungo was quite an interesting fellow.

LikeLike

Indeed!

But I am afraid that I do not have a copy of the entire publication…

LikeLike

Oh, I wouldn’t expect so – am just talking to myself (out-loud). One of the down-sides of living here, is the lack of available library sources except on the web!

LikeLike

But if I had it, I’d gladly share it 🙂

LikeLike

Oh thanks – perhaps with open access growing, such docs will eventually be available…

LikeLike

Well, your comment made me curious and look what I found: http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/p/park/mungo/index.html

LikeLike

Such and interesting post Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you, Rita!

LikeLike

Pingback: More Adventures of Mungo Park, Who Describes Hunger Crops in the Western Sahel, 1797 | Sril Farms

Thank you for reposting!

LikeLike