,,

,,Bread was the central element of cuisine and daily nourishment in Ancient Egypt, from the very poorest through the nobility. Today, bread is commonly known as ‘aysh in Egypt, meaning ‘life’ in Arabic. In the Old Kingdom, so-called rectangular slab stelae regularly picture the deceased seated in front of a table laden with bread, while additional offerings are enumerated in the accompanied registers. It is bread, however, that is always central:

Manuelian g 1201 Slab stela of Wepemnefret in Giza West Cemetery mastaba. Wepemnefret seated in front of a presentation table of bread. Source – Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, Berkeley, 6–19825. Photograph by Bruce White. Future blogs will discuss slab stelae and other means of portraying and discussing bread.

Several millennia later, along the Nile Valley, bread continued being the key dietary component – as antique and ancient Egyptian cuisines and life-styles were gradually replaced by Coptic orthodox churches and general Coptic life-styles – a transformation that began in the late first century CE [Current Era].

In this blog I want to focus on the latter – on the role of holy bread – or qurbaan/’urbaan – which is the key culinary component of Coptic religious life and liturgy. Then, in later blogs, I shall look at the production and consumption of bread in earlier periods of Egyptian history, beginning with the slab stelae of the Old Kingdom, and what these representations and accompanying texts might tell us about society, agriculture and cuisine of these periods and places along the Nile Valley.

This is a very enjoyable journey, for I have studied and have various levels of skill in all forms of language in Egypt – from earliest forms of hieroglyphic writing and syntax, through modern colloquial Egyptian, which I spoke fluently in Egypt during my years of doctoral research and later work; pretty rusty now, though. I also want to thank William Rubel for suggesting such an interesting chance to pursue this venture – following the historical path of bread along the chain of grain and bread that is linked to the Nile Valley; great fun and a bit of a challenge!

First, however, let’s look at a bit of linguistic history regarding the words Copt/Coptic, Egypt and Gypsy – all of which are related and are derived from ancient Egyptian words – with the first two providing the central historical frame for the emergence and transformations of ‘bread’ during the long story of cuisine in the Nile Valley. To help unravel the meanings of these words, here is some of the work by A.K. Ayma on their etymology:

Egypt, Copt/Coptic, Gypsy

Egypt derives from Latin Aegyptus, which in turn goes back on the Greek name for the Nile country: Aiguptos. This name originally seems to have been one of the names of Memphis, the capital of the country, a name that later came to denote the entire land by pars pro toto.

For the Greek Aiguptos was derived from [ancient egyptian] Hy.t-k3-ptH (Haykuptah)(= “Mansion of the ka, i.e. life force, of Ptah”) – the name of the Ptah temple in Memphis, a name which first came to denote also the city area around the temple, and finally was extended to the whole city of Memphis; as such it appears in cuneiform records as name for the city: Khi-ku-up-ta-akh (Hekuptah).

Already in the Mycenean/Cretan Linear B tablets (13th c. BC), the personal name a-ku-pi-ti-yo (Aikupitiyo, i.e. Aiguptios, “the Egyptian”) is attested (Talanta XXVIII/XXIX, p.157). Note that Hy.t (*Hayit) is a variant of the more usual Hw.t or H.t (see Vycichl p. 5, 287, 519).

The Greek aiguptios (= “Egyptian”) was later borrowed, via a shortened form *gupti, into Arabic as qibti (in local Theban dialect also: qubti), and into the jewish Talmud as gifti (cf. Loprieno p. 241; Vycichl p.5). Because of this the native (non-Arabic and Christian) Egyptians were called Qibti or Qubti – from which derives our Copt.

The mysterious nomads who appeared in Europe in the late 15th c. AD, and in reality (i.e. linguistically) did stem from India, were associated with the far and mysterious Egypt, and therefore called Gyphtoi (in Greece) and Gypsies (in England, older form Gypcian, short for Egipcien “Egyptian”), names that are corruptions of Latin Aegypti (“Egyptians”).

Source: A.K. Eyma – Egyptian Loan Words in English, version 17 (March ’07).

A few words on the Coptic Alphabet, by Geoffrey Graham

So how is Coptic different from earlier forms of the ancient Egyptian language? Here are some thoughts by Geoffrey Graham, and more details are to be found on the AEL site

[web addresses to follow – lots of internet problems today…]

Let me … introduce the Coptic Alphabet (yes it is an alphabet, much easier than ancient Egyptian!) and the pertinent phonology: The Coptic Alphabet was borrowed from Classical Greek, at some time before the development of Koine Greek, although the records of its early development have not yet been found. This means that the phonology of Coptic’s usage of the Greek alphabet reflects the kind of Greek spoken about 200 BC, rather than the period at which Coptic seems to first appear in our records, about 200 AD! …

… That is the Coptic Alphabet as it comes to us in the Sahidic Dialect. Other dialects have a few additional characters, but one generally begins with Sahidic, and this should suffice for now. The first section of letters are all borrowed from the Greek alphabet, and the last six were adopted from the Demotic Script, the native form of writing used in Egypt…

… I am offering a brief anecdote from the Apothegmata Patrum “Tales of the Desert Fathers“. It is very short, and possibly a little simplistic. I will try to explain what is going on so that people will have a taste of what the last stage of Egyptian sounded like…

Here it goes:

- “The devil transformed himself in an angelic costume of light.”

- “He appeared to one of the brothers and he said to him; “I am

Gabriel- “But he said to him: “Look, you you must have been sent unto

another one of the brothers,- “And, as for him, then he disappeared.”

Source: <geoffrey.graham@yale.edu> A Coptic Anecdote, on AEL

As a short saying from The Desert Fathers, I think this is actually quite a pithy and multi-layered piece – not ‘simplistic’ as suggested by Graham; more on that later.

. . . . .

Okay, now that we’re in linguistic harmony with the substrate of our subject, let’s look at several pictures taken in or before 1930 that document bread production in the monasteries of Saint Paul and Saint Anthony, located in the Red Sea Desert. I have selected these to show not only the production of Coptic bread, which is highly ritualized, but also to depict some of the more general features of monastery cuisine. As far as I know, these are the earliest pictures of bread and food production in Coptic monasteries of Egypt.

These (and other) Coptic monasteries in Egypt were generally self-sufficient both in the production of foods – both in the monastery walls and in plots that they may have farmed in the Nile Valley – as well as in the processing of these foods.

St Paul (Deir Anbba Bula) mid 19th century or earlier. Source – http://www.touregypt.net

General view of the Monastery of Saint Anthony. Source – Dumbarton Oaks

The Abbot in the library of St.Paul. I am intrigued by what appear to be quite modern, white tabs on which call numbers would be written. Was this one of the introductions of Whittemore’s expedition? Source – Dumbarton Oaks

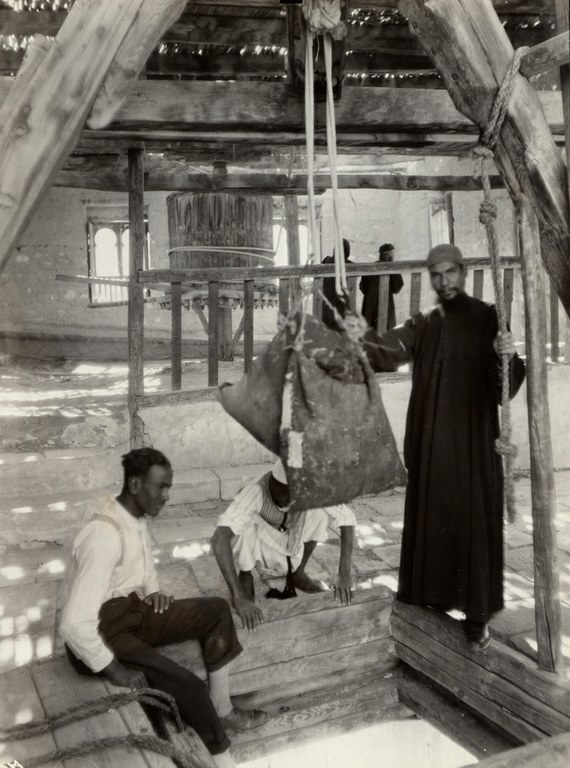

St. Anthony’s Monastery mill room. I am unaware of any other working mills in Egypt – though there have been some excavations in the Fayum that I’ll talk about in a later blog. the mill and related components are being renewed by ARCE. Source – The American Research Center, Egypt [ARCE]

Local men making bread St.Anthony. Difficult to explain the activities here, because of angle and lighting of the picture . Source – Dumbarton Oaks

Monk stamping the Holy Bread, St.Anthony. Coptic stamps are a key part of the production and baking process, having its own meanings that I’ll discuss later. Source – Dumbarton Oaks

Monks baking the Holy Bread, St.Anthony. Source – Dumbarton Oaks

Baking the Holy Bread, St.Paul. Note similarity of the oven and also of the confirmation of the loaves and baking process with St. Anthony, in the above picture. Source – Dumbarton Oaks

Monks sorting dried grapes,Monastery of St Anthony 1930. Important source of little ‘sweets.’ Source – D.Barton Dumbarton Oaks

Monk roasting coffee, St.Anthony. Source – Dumbarton Oaks

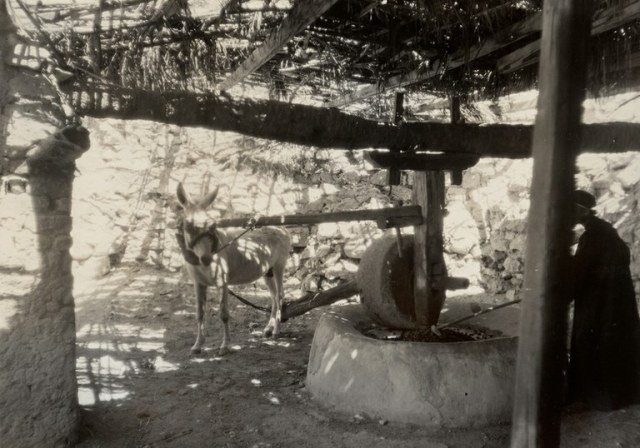

Olive oil mill, St.Anthony. Similarly designed mills can be found in other parts of Egypt [excavations] and across North Africa. Source – Dumbarton Oaks

Refectory, St.Anthony. During meals, readings were given. Source – Dumbarton Oaks

Group portrait of monks, St.Paul. Source – Dumbarton Oaks

Through adherence to precise rituals associated with making and baking, whether the preparation and baking is found in Egypt or elsewhere, this holy bread transcends local environmental and cultural characteristics that are generally associated with specific breads and their production.

Just before baking, each loaf is pierced five times around the center stamp, symbolizing the wounds on Christ – who on the loaf is symbolized by the central feature of the stamp. Source – http://www.st-mary

Making qurbaan [Coptic holy bread] – طريقة عمل القربان

The following two videos are on the production of qurbaan. It is interesting that the process not only is highly ritualized, but also that it is conducted by men. The first video has quite a good description and depiction of how the bread is made – spoken in colloquial Egyptian by a priest, with english subs.

A film of The Red Sea Monasteries of Egypt made during the expedition of Thomas Whittemore to these monasteries:

The first official project undertaken by the Byzantine Institute [Dumbarton Oaks] was the examination and documentation of wall paintings in the Red Sea Monasteries in Egypt, which occurred between 1929 and 1932. Filmed in 1930, the below film was likely recorded during the First Expedition (1929-1930) to the Red Sea Monasteries and it includes scenes from both monasteries of Saint Paul and Saint Anthony.

Source: Dumbarton Oaks

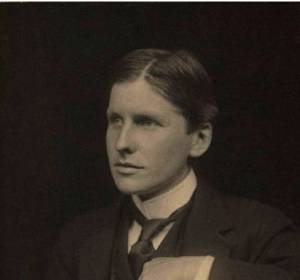

Two expeditions were organized and led by Thomas Whittemore into the Eastern Desert of Egypt to study the two monasteries discussed in this blog. I would like to do a later piece on this intriguing figure and his work.

Whittemore’s expedition, before leaving the Monastery of Saint Anthony, Egypt, 1930-1931 . Source – Dumbarton Oaks. I’m trying to put this picture in as the header image, but so far no luck. Will keep trying….

Thomas Whittemore is perhaps best remembered for founding the Byzantine Institute [at Dumbarton Oaks], an organization that specialized in the study, restoration, and conservation of Byzantine art and architecture, in 1930. Overseeing the Institute’s fieldwork projects and publication efforts until his sudden death in 1950, Whittemore made a name for himself among Byzantinists and art historians alike when he initiated an unprecedented restoration and conservation project at Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey, in December of 1931.

How an English professor and amateur archaeologist from the United States convinced the Turkish government to permit an international team of fieldworkers to restore and conserve the building’s priceless mosaics—to convert what was at the time a mosque into a worksite and subsequently a museum—remains something of a mystery.

So, how did Whittemore make his way to Turkey? How did he, moreover, manage to create and sustain a complex organization like the Byzantine Institute in the midst of the Great Depression, a time in which introversion was the way of the West? Why, for that matter, did he turn his eyes toward Byzantium?

Source – Dumbarton Oaks

FILM SEQUENCE

- Film starts with general exterior views of the monastery of Saint Paul

- Men preparing food and performing day-to-day activities

- Thomas Whittemore [head of the expedition] and unidentified individuals on camels

- General exterior views of the monastery and surrounding landscape

- Men digging a waterway

- Film ends with general views of the surrounding landscape

The Cave Church of St. Paul marks the spot where St. Anthony, “the Father of Monasticism,” and St. Paul, “the First Hermit,” are believed to have met. It is a sacred place representing the very beginning of Christian monasticism.

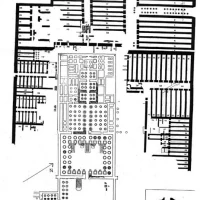

In 1997, work began at St. Paul’s Monastery to conserve the mill building, refectory and eighteenth-century enclosure wall. This site, visited by Coptic pilgrims as well as tourists interested in the historic attributes of the place, contains vestiges of its past life as a self-sufficient community.

The mill building has special significance as the source of the flour for the bread that is such an important part of the monks’ daily life.

ARCE announces the publication of a new book, “The Cave Church of Paul the Hermit at the Monastery of St. Paul in Egypt,” which is available now through Amazon.com. The volume is co-published by the American Research Center in Egypt and Yale University Press.

The collection of essays written by renowned specialists and edited by William Lyster presents different aspects of the Coptic Monastery of St. Paul on the Red Sea coast of Egypt and of its main church. The church evolved from a rock-cut hermit’s cave as early as the 4th century, and is richly decorated with wall paintings dating from the early 13th to the 18th century.

Thanks for sharing. I visited St. Anthony in 2004 and was unable to visit St. Paul, as it was closing as I arrived. Wonderful historic images. Really enjoyed this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this post and sharing these historic photos. I was able to visit St. Anthony’s in 2004, and arrived too late the same day at St. Paul’s. It left a profound impression on me. I have seen and heard how Bishoi Monastery has been attacked by the army after the fall of Mubarak and now wonder how these two more remote sites have fared. I need to find a sample of this bread.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Diana, I hope you and your colleagues are recovered. Bad water is no joke. And this is a great post. On the mystery photo of men and a sack, are they not high in the mill pulling up the sack of wheat so that they can feed it into the hopper to go down to be ground? Not that I’m an expert.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Rachel – for sure I’m not an expert on this either; your suggestion sounds quite reasonable, though. Anyone else have thoughts on this?

LikeLike

PS I was also interested that you mention the Linear B Script writings which is what I am learning at the moment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rita – thought that you would like that – included it for you!

LikeLike

Oh Gee thanks Diana !!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Diana, This is truly a fascinating post I must thank you for sharing. Love the photo’s of the Monks baking and stamping the bread. The view of the Monastery of St Anthony and the Abbot in the library. Wonderful !!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Rita, and I’m glad that you enjoyed it~!

LikeLike