This blog follows on Gambler’s House interesting Blog about Filed Teeth at Cahokia :

One of the distinctive characteristics of Cahokia and its area of strong influence is the prevalence of filed teeth in many human burials. Filing of teeth as a cultural practice was common in Mexico for thousands of years before the Spanish conquest, but further north it is very rare and found mostly at Cahokia and sites in the immediately surrounding area.

The following blog provides the kind of information that is available on teeth-filing in Africa, as described by 19th century explorers. A following blog will focus on analysis of this and related practices.

————–

Colonial explorers of the 19th century were both amazed and generally repulsed by the variety of body scarifications and adornment that were practiced throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Tattooing and teeth-filing seem to have been the most common, with nose and ear plugs, and hair styling, also an important indicator of ethnicity and relative social status.

Descriptions of these practices played an important part in both popularizing the books written by the explorers, as well as providing yet more rationale for colonial intervention in the continent. For example, one of the many descriptions of bodily scarifications by Richard Burton states that:

…the population about Nkulu seemed to be a very mixed race. Some were ultra-negro, of the dead dull-black type, prognathous and long-headed like apes; others were of the red variety, with hair and eyes of a brownish tinge, and a few had features which if whitewashed could hardly be distinguished from Europeans.

The tattoo was remarkable as amongst the tribes of the lower Zambeze [River in south-central Africa]. There were waistcoats, epaulettes, braces and cross-belts of huge welts, and raised polished lumps which must have cost not a little suffering; the skin is pinched up between the fingers and sawn across with a bluntish knife, the deeper the better; various plants are used as styptics, and the proper size of the cicatrice is maintained by constant pressure, which makes the flesh protrude from the wound.

The teeth were as barbarously mutilated as the skin; these had all the incisors sharp-tipped; those chipped a chevron-shaped hole in the two upper or lower frontals, and not a few seemed to attempt converting the whole denture into molars.

Burton, Richard – Two Trips to Gorilla Land and the Cataracts of the Congo Volume 2, 1876

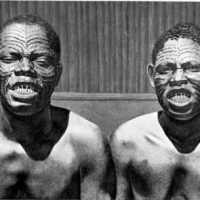

- Tribespeople of Bopoto, Northern Congo with sharpened teeth (c. 1912) – Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston

The views of Sir Samuel Baker, on the other hand, were amongst the more reasonable by way of descriptions and explanations:

It is difficult to explain real beauty. A defect in one country is a desideratum in another. Scars upon the face are, in Europe, a blemish; but here [in central Africa] and in the Arab countries no beauty can be perfect until the cheeks or temples have been gashed.

The Arabs [of eastern Sudan]make three gashes upon each cheek, and rub the wounds with salt and a kind of porridge (asida) to produce proud-flesh; thus every female slave captured by the slave-hunters is marked to prove her identity and to improve her charms. Each tribe has its peculiar fashion as to the position and form of the cicatrix.

Baker, Samuel – In the heart of Africa, 1861

David Livingston, too, provided less spectacular descriptions of these practices, and as a researcher noted, ” He states things as he sees them, and notes that the Africans are, like all other men, a curious mixture of good and evil…” (Alan R. Light, 1997) :

The people who came with Sheakondo to our bivouac had their teeth filed to a point by way of beautifying them, though those which were left untouched were always the whitest; they are generally tattooed in various parts, but chiefly on the abdomen: the skin is raised in small elevated cicatrices, each nearly half an inch long and a quarter of an inch in diameter, so that a number of them may constitute a star, or other device. The dark color of the skin prevents any coloring matter being deposited in these figures, but they love much to have the whole surface of their bodies anointed with a comfortable varnish of oil.

Livingstone, David – Missionary Travels and Researches in Southern Africa, 1857

Filed teeth of Queen Moari, Livingston, Last Journals, vol 1, 1866-68

Henry Barth, as well, described local practices in west Africa in a more reasonable way:

…But besides the Sugurti there happened to be just then present in the village some Budduma, handsome, slender, and intelligent people, their whole attire consisting in a leathern apron and a string of white beads round the neck, which, together with their white teeth, produces a beautiful contrast with the jet-black skin.

Barth, Henry – Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa, 1890

Henry Morton Stanley, a previous newspaper reporter before heading of to Africa to ‘discover’ Livingstone, wrote texts that were guaranteed to thrill readers of the time and to confirm the need for European intervention:

…. The Wahyeya are also partial to ochre, black paints, and a composition of black mud, which they mould into the form of a plate, and attach to the back part of the head. Their upper teeth are filed. “out of regard to custom/’ they say, and not from any taste for human flesh.

When questioned as to whether it was their custom to eat of the flesh of people slain in battle, they were positive in their denial, and protested great repugnance to such a diet, though they eat the flesh of all animals except that of dogs.

…The savages were not unpleasant to look at, though the prejudices of our people made them declare that they smelled the flesh of dead men when they caught hold of their legs and upset them in the road ! Each man’s upper row of teeth was filed, and on their foreheads were two curved rows of tattoo-marks; the temples were also punctured.

Katembo questioned them, and they confessed that they lay in wait for man-meat…

…It was very curious to watch this transition from one tribal peculiarity and custom to another. It was evident that these tribes never traded with those above. I doubt whether the people of Urangi and Eubunga are cannibals, though we obtained proof sufficient that human life is not a subject of concern with them, and the necklaces of human teeth which they wore were by no means assuring — they provoked morbid ideas.

… As for Frank and myself, our behaviour was characterized by an angelic benignity worthy of canonization. I sat smiling in the midst of a tattooed group, remarkable for their filed teeth and ugly gashed bodies, and bearing in their hands fearfully dangerous-looking naked knives or swords, with which the crowd might have hacked me to pieces before I could have even divined their intentions…

Mubarik Bombey, who served with Livingstone, Speke and Stanley, the latter having this to say of him "at his first appearance, I was favourably impressed with Bombay, though his face was rugged, his mouth large, his eyes small, and his nose flat. Source: Royal Geographic Society.

Stanley, Henry Morton – Through the Dark Continent, 1876

Speke, whose adventures were before those of Stanley, had this to say about Mubarik Bombey:

The man of quaintest aspect in it is Sidi Mabarak Bombay. He is of the Wahiyow tribe, who make the best slaves in Eastern Africa. His breed is that of the true woolly-headed negro, though he does not represent a good specimen of them physically, being somewhat smaller in his general proportions than those one generally sees as stokers in our steamers that traverse the Indian Ocean. His head, though woodeny, like a barber’s block, is lit up by a humorous little pair of pig-like eyes, set in a generous benign-looking countenance, which, strange to say, does not belie him, for his good conduct and honesty of purpose are without parallel.

His muzzle projects dog-monkey fashion, and is adorned with a regular set of sharp-pointed alligator teeth, which he presents to full view as constantly as his very ticklish risible faculties become excited.

Speke, John H. – What Led To the Discovery of the Source Of The Nile, 1864

In addition to filing teeth, extraction of several teeth either above or in the lower jaw was wide-spread in sub-Saharan Africa:

To-day we slaughtered and cooked two cows for the journey – the remaining three and one goat having been lost in the Luajerri— and gave the women of the place beads in return for their hospitality. They are nearly all Wanyoro, having been captured in that country by king Mtesa and given to Mlondo.

They said their teeth were extracted, four to six lower incisors, when they were young, because no Myoro would allow a person to drink from his cup unless he conformed to that custom. The same law exists in Usoga. they showed me the place they assigned for your camp when you come over there.

Speke, John H. – What Led To the Discovery of the Source Of The Nile, 1864

In west Africa, the Lander brothers attempted to discover Timbuctoo as well as the course of the Niger River. Their narratives are less bellocost than those of East African explorers:

[In Houssa Land] – The chief’s eldest son was with them during the greater part of this day. The manners of this young man were reserved, but respectful. He was a great admirer of the English, and had obtained a smattering of their language. Although his appearance was extremely boyish, he had already three wives, and was the father of two children.

His front teeth were filed to a point, after the manner of the Logos people; but, notwithstanding this disadvantage, his features bore less marks of ferocity than they had observed in the countenance of any one of his countrymen, while his general deportment was infinitely more pleasing and humble than theirs.

When asked whether, if it were in his power to do so, he would injure the travellers, or any European, who might hereafter visit Badagry, he made no reply, but silently approached their seat, and falling on his knees at their feet, he pressed Richard Lander with eagerness to his soft naked bosom, and affectionately kissed his hand. No language or expression could have been half so eloquent.

Huish, Robert – Lander’s Travels: The Travels of Richard and John Lander into the Interior of Africa, 1836

These practices now seem to be abandoned, except, perhaps, in a few locations – cf. photos below that were taken in Angola of two young women – I am trying to find out their source.

Until recent times, scarifications of the body and teeth-filing were widespread across the continent, and can be explained both in order to enhance beauty as well as to identify ethnic group. As well, perhaps, as a part of attaining adulthood.

There are a few other aspects of these practices that I’ll take up in another blog.

Related articles

- Explorers of the Nile – The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure – By Tim Jeal – Book Review (nytimes.com)

- Cuisines and Crops of Africa – Imagining Cannibalism in the 19th Century and Now (dianabuja.wordpress.com)

Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/mytripsmypics/5102125985/

Pingback: In Rio: Remembering the New Blacks - Black Diamonds

Pingback: Dead Men Tell Long Tales | Sharing Forever Together

Pingback: 2014 in review | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, The Middle East, Agriculture, History and Culture

Thanks for finally talking about >Teeth-filing as

a Mark of Beauty and Belonging in 19th Century Africa | DIANABUJA’S BLOG: Africa,

The Middle East, Agriculture, History and Culture <Loved it!

LikeLike

Thanks to you, too!

LikeLike

Pingback: 2013 in review | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, The Middle East, Agriculture, History and Culture

The people of Central Africa who make their teeth pointy today do not file them. This is done with percussion. Frankly, I doubt that the practice involves filing very often. Files are not common in traditional tool kids, and grinding (the closes thing) would not do well on teeth.

LikeLike

Thanks for your input. Pre-modern files made of obsidian are not difficult. Don’t have the references right here, though. Filing is depected being used in pre’modern central America. ‘Filing’ is a generic term and other terms include chisling, chipping, modification, sharpening, mutilation, notching, etc. In all my years living-working in central Africa (based in Burundi) have not seen (or heard of) teeth modification. But then again, the Congo is huge and there are many ethnic groups.

LikeLike