When I began working in the agriculture-agroforestry-livestock sectors, the main paradigm for improvement was that of technology transfer – moving technologies developed and used in the northern (western) hemisphere, to researchers and farmers in the South.

ToT (Transfer of Technology), as it is called, was considered the avenue for improvement, by which cultivars and improved livestock that had been developed in the North would be ‘transferred’ to the southern hemisphere.

Neat and clean. No culture – no society – no politics – no history: only ‘technology’.

I remember a soil scientist explaining to me:

“There are so many technologies just sitting on the shelf, waiting to be transferred!”

He continued:

“We just need to get them out to the researchers and farmers!”.

And so, extension agencies, by which ‘technical packages’ were provided, to farmers, became one of the ‘answers’. Sadly, as time went by and failures mounted, this approach was seen to be far too simplistic. Technologies cannot exist outside of a social-cultural-economic-political context. And thus, it becomes incumbent upon those developing new or improving old methods to consider the clients – the farmers and policy makers – their limitations, needs, resources, and demands; the context in which they lived and operated.

A major turning point in achieving this came with the work of Robert Chambers and his colleagues, who in the early 80’s developed Rapid Rural Appraisals, and then Participatory Rural Appraisals (RRAs; PRAs) in which assessments of local resources and needs were conducted with local farmers. In this way, farmers became not the object of research, but ‘researcher’s themselves, working with a multidisciplinary team to define major problems and sort out possible solutions.

This is a radical shift – called by some a new paradigm – that entails enjoining researchers and technicians with local community members in ways that go beyond filling in of a questionnaire or conducting surveys by outsiders. A brief review is given here and an articles by Chambers here.

While working with an afforestation-antidesertification project in western Sudan, with our donor we were able to bring Robert Chambers and several of his colleagues to Sudan for training. Details of that project, which benefitted greatly from Chamber’s training, can be found here and here.

While the method has come under criticism and now its limitations are better recognized, I continue to find it an exceptionally useful tool to get researchers, technicians, local farmers, and project staff working together, speaking ‘the same language’, and jointly determining both the most crucial issues as well as potential solutions within the confines of a particular project.

Here follows information on one of the training activities conducted upcountry, with Lutheran World Service technical staff and members of a local village. Photos of several past blogs are used here; they are for explanatory purposes.

Joint meetings at the end of the day, to discuss what had been accomplished and activities for the next day

Of course, it is only a first step – but one that can avoid any number of wrong directions while also bringing on board the ‘objects’ of research and development – farmers and herders themselves.

Transects – an example of farmer-led research:

Transects of farms are conducted by farmers together with technical team members. A transect is walked across an area of the farm, and different data are noted, taking the lead from how farmers (not technicians) perceive the categories. The transects are later drawn up by the farmers together with technicians and researchers.

With women of the colline and a technical assistant, during the assessment

In training that I have been conducting upcountry, teams are divided into men and women, because the farming activities are very much gender-specific and so transects of the same area, conducted by each gender, can be quite different.

Farms are usually situated on a hill (as in the distance), with different crops and trees planted in horizontal ‘bands’ that differ as one moves down the plot.

A team of local women and several project technical staff walked a transect on the farm of one of the women, after which the women drew their own transect noting characteristics such as soil type, crops grown, major problems, major opportunities.

A group of women drawing their transect after returning from walking along it.

A group of men also have walked a transect and are now busy discussing and drawing it. Men will come up with a different set of problems and solutions that women, with regard to particular crops, grasses or trees.

A local group of men discussing and filling out their transect

Back at the project office, staff continued to discuss and debate preliminary findings and how they could best be incorporated into project work.

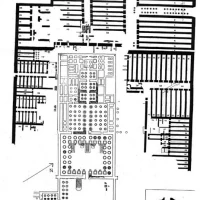

Differences and similarities between findings of men’s (left) and women’s (right) transects are identified and discussed.

Market days take place two times a week, and these are also important occasions to find out what villagers sell, and during which times of the year. In this area, the closest market is a four mile walk and with no transport other than ‘head’, market access came out as a top priority – especially, how to diversify sales so as not to be dependent only on one merchant in one market for sales.

For example, it makes little sense to assist farmers in increasing their output of (e.g.) sweet potatoes, if there are no markets to which they can readily sell excess.

traffic from a local market – women are transporting BaTwa (pygmy produced) pots, which are used in local beer production and cuisines.

What kinds of things did we learn, and where to go after such an assessment? More on that, in the future.

Related articles

- Bag it: Protecting crops in Africa (one.org)

- Food Aid: Feeding Bellies, Starving Markets? (fellowsblog.kiva.org)

am interested

LikeLike

On FB, Noelle Jacqueline Ingledew asks about the applicability of PRA methods with health issues. It is widely used with health and nutrition, and here are just a few links:

Click to access article_print_553.pdf

Click to access copyright%20IJAR_2_06_Preece.pdf

Click to access 3rd_day2_12_kumar.pdf

Click to access plan_01602.PDF

Click to access plan_01608.PDF

LikeLike

very insightful, diana

that’s a huge project you’re working on

LikeLike

Thanks, Maria. Actually, it does not seem such a huge project; activities are broken up into discrete tasks. Part of the planning process!

LikeLike