Just as people and spirits must be fed, so, too, is the case with the soils that are to be cultivated. Hence, magically based recipes that are specially destined to nourish the soils and/or spirits associated with a woman’s garden plot were common features of smallholder agriculture as described to the Rev. Robert Nassau in the late Nineteenth Century.

The following example of such a magical recipe for garden soils is complicated – not only with regard to specific wild ingredients, but also in terms of procedures and products to be used and/or hidden.

While it is unclear which of the social groups residing in the Ogowe Watershed in West Africa used this particular recipe, it is probable that similar magical recipes for soils and their spirits were to be found in the area.

We would like to know more: was the dish to feed the spirits of the soil, the ancestors of the women who looked after her garden, or was this aspect of the recipe – who were to be the major recipients of the stew – well explained in local lore?

Now, of course, this process has been largely secularized. Concoctions placed on the soil of women’s garden plots tend to be either fertilizers or insecticides. An example of this in our own gardens here on the north shore of Lake Tanganyika is given at the bottom of the blog.

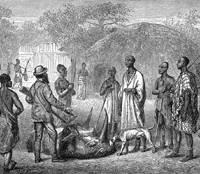

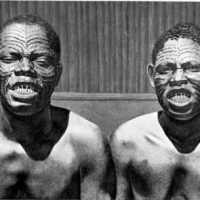

While women do the gardening, men are responsible for tending The palm trees in the gardens. Source – Mary Kingsley, West African Studies, 1899.

Here is what the Rev. Nassau has to say –

Planting is accomplished almost entirely by women:

A man assists his wife in the clearing of the forest for a garden plot; but she and her servants attend to the planting, weeding, and other working of the garden itself- If a woman says to herself,

- “I want to have plenty of food!”

- “I will make medicine for it!”

- She proceeds to gather the necessary ingredients.

- She takes her ukwala (machete), pavo (knife), short hoe (like a trowel), and elinga (basket), and goes to the forest.

- She must go very early in the morning, and alone.

- She gathers

- a leaf called “tubĕ,”

- another called “injĕnji,”

- the bark of a tree called “bohamba,”

- the bark also of elâmbâ, and

- leaves of bokuda.

- Hiding them in a safe place, she goes back to her village to get her earthen pot.

- Returning with it to the forest,

- She makes a fire, not with coals from the village, but with new, clean fire made by the two fire-sticks.

- (These [fire sticks], used by natives before steel and flint were introduced, require often an hour’s twirling before friction develops sufficient heat to cause a spark. The sparks are caught on thoroughly dried plantain fibre.)

- Then she builds her fire.

- She goes to some spring or stream for water to

- Put in the pot with the leaves and barks, and sets it on the fire.

- All this while she is not to be seen by other people.

- When the water has boiled, she sets the pot in the middle of the acre of ground which she intends to clear for her garden until its contents cool.

- In the meanwhile she goes to some creek and gets “chalk” (a white clay is found in places in the beds of streams).

- She washes it clean of mud and rubs it on her breast.

- Then she takes the pot, and empties its decoction by sprinkling it, with a bunch of leaves, over the ground, saying,

- “My forefathers! now in the land of spirits, give me food!

- “Let me have food more abundantly than all other people!”

- Then she again sets the pot in the middle of the proposed plantation.She takes from it the tubĕ leaves and puts them into:

- Four little cornucopias (ehongo), which she rolls from another large leaf of the elende tree.

- She sets these in the four corners of the garden.

- Whenever she comes on any other day to work in the garden,

- she pulls a succulent plant,

- squeezes its juice into the ehongo; and

- this juice she drops into her eye.

- To be efficient, this medicine has a prohibition connected with it, viz., that during the days of her menses she shall not go to the garden.

- When her plants have grown, and she has eaten of them, she must break the pot.

- Having done so, she makes a large fire at an end of the garden, and

- burns the pieces of earthenware so that they shall be utterly calcined.

- It is not required that she shall stay by the fire awaiting that result. She may, if she wishes, in the meanwhile go back to her village.

- She takes the ashes of the pot,

- mixes them with chalk in a jomba (bundle) of leaves, which

- she ties to a tree of her garden in a hidden spot where people will not see it.

- Another strict prohibition is required of her by the medicine, viz., that she is not to steal from another woman’s garden.

- If she breaks this law, her own garden will not produce.

- The jomba is kept for years, or as long as she plants at that place, and

- the chalk mixture is rubbed on her breast at each planting season.

- From time to time also, as the leaves of the jomba decay or break away, she puts fresh ones about it, to prevent the wetting of its contents by raid or its injury in any other way.

Dabbing each plant with a small amount of goat dung slurry at our contract farming site. However, there are no magical ingredients in this slurry – only goat dung. It is a common method by which smallholders fertilize their crop.

Text source – Fetichism in West Africa; Forty Years’ Observation of Native Customs and Superstitions, by the Rev. Robert Hamill Nassau. University Press, Cambridge, U.S.A. 1904.

Other entries in this series are:

- The Magicality of Cuisine 1: Meat Cooked in Plantain Leaves as a Love Philtre, 19th Century Gabon, West Africa

- The Magicality of Cuisine 2: A Recipe for a complicated Love Filtre for Men. 19th Century Gabon

- The Magicality of Cuisine 3: A Dish of Fish and Plantains to Guarantee Successful Fishing, 19th Century Gabon, West Africa

Pingback: Sacred Huts and Magical Aspects of Food | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, The Middle East, Agriculture, History and Culture

Pingback: The Magicality of Cuisine 5 – A Spicy Warriors’ Stew, Gabon West Africa | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, The Middle East, Agriculture, History and Culture