[First posted 24 Oct 2009 Revised 04 November 2011]

With the Horn of Africa so much in the news now, I am updating and reposting several links that focus on limited resources in the area.

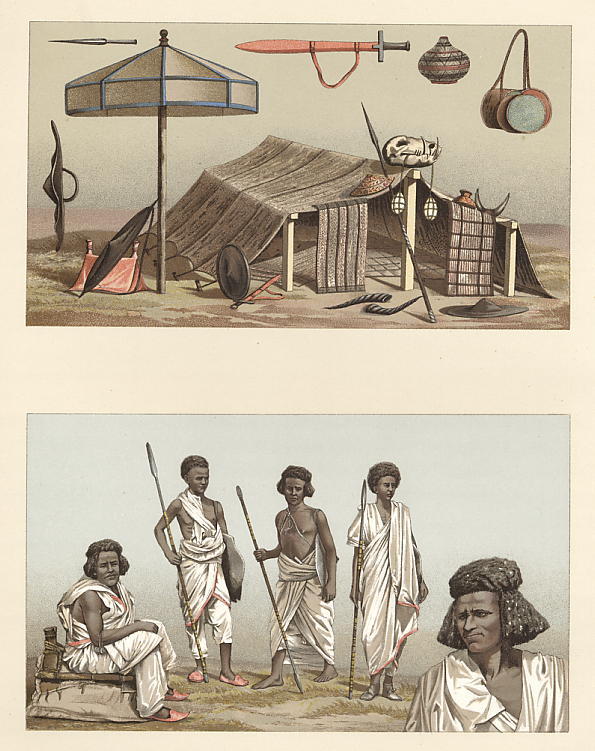

Summary: The importance of the relationship between a particular environment on the one hand, and the agriculture-livestock-cuisines found therein on the other, has been minimized in modern times. This is due largely to the ability of industrial agriculture to provide a variety of technologies that often distance the linkages between environment and livelihoods – both of people and animals. The results can be catastrophic in extremely marginal areas, as in the Horn of Africa. Photo: 1882. From E.Cerulli, Somalia, Scritti Vari Editi ed Inediti, Vol. 1When the British explorer John Hanning Speke traveled through what is today Somalia, East Africa, in the 19th. Century, he was very impressed both by the eating habits of the local people, as well as by the physical characteristics of livestock – both of which he attributed to living in a harsh desert climate:

What Led To The Discovery of the Source Of The Nile, by John Hanning Speke, 1864

Their food is very limited [Somali bedouin], except in the rainy season, when milk prevails: in consequence of this, it being now the dry season, my servants accounted for their increasing appetite for my dates. Some of the poorer men are said to pass their whole lives without tasting any flesh or grain, but to live entirely on sour milk, wild honey, or gums, as they may chance to come across them…

As a gun is known by the loudness of its report, and ability to stand a large discharge of powder, to be of good quality, so is a man’s power gaged by his capacity of devouring food; it is considered a feat of superiority to surpass another in eating.

I have seen a Somali myself, when half-starved by long fasting, and his stomach drawn in, sit down to a large skinful of milk, and drink away without drawing breath until it was quite empty, and it was easy to observe his stomach swelling out in exact proportion as the skin of liquor decreased…

Each man carried a junk of flesh, a skin of water, and a little hay, and was then ready for a long campaign, for they were not soft like the English (their general boast), who must have their daily food; they were hardy enough to work without eating ten days in succession, if the emergency required it. Here a second camel was on the point of dying, when his flesh was saved from becoming carrion by a knife being passed across his throat…

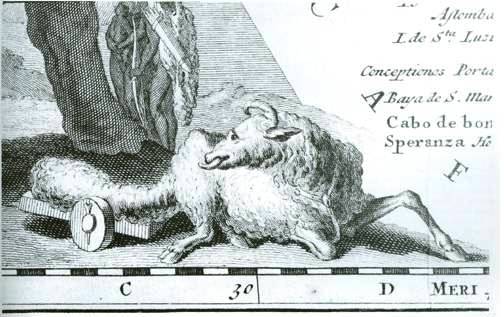

I was very much struck with the sleekness of the sheep, considering there appeared nothing for them to live upon; but I was shown amongst the stony ground here and there a little green pulpy-looking weed, an ice plant called Buskale, succulent, and by repute highly nutritious. It was on this they fed and throve.

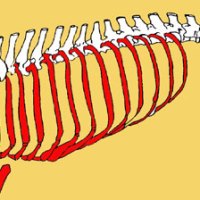

These Dumba sheep–the fat-tailed breed–appear to thrive on much less food, and can abstain longer from eating, than any others. This is probably occasioned by the nourishment they derive from the fat of their tails, which acts as a reservoir, regularly supplying, as it necessarily would do, any sudden or excessive drainage from any other part of their systems…

The ancestors of these fat-tailed sheep may originally have come from Arabia, where for millennium they were an important asset of pastoral tribes both in Arabia as well as in the Middle East.

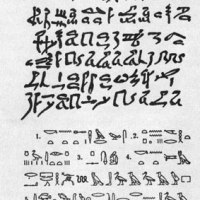

Rock engravings of fat-tailed sheep from central Arabia, second or early first millennium BC. Source FAO, Anati, 1968

Herodotus mentions them in Arabia in the 5th Century:

Herodotus, Histories, Book II, Tr. by Rawlinson:

There are also in Arabia two kinds of sheep worthy of admiration, the like of which is nowhere else to be seen; the one kind has long tails, not less than three cubits in length, which, if they were allowed to trail on the ground, would be bruised and fall into sores. As it is, all the shepherds know enough of carpentering to make little trucks for their sheep’s tails. The trucks are placed under the tails, each sheep having one to himself, and the tails are then tied down upon them. The other kind has a broad tail, which is a cubit across sometimes.

The importance of relationship between a particular environment on the one hand, and the agriculture-livestock-cuisines found therein on the other, has been minimized in modern times. This is due largely to the ability of industrial agriculture to provide a variety of technologies that often distance the linkages between environment and livelihoods – both of people and animals.

For example, improved irrigation allows for less drought-resistant crops and livestock – while high medications that treat various livestock diseases and parasite problems can make possible the raising of non-indigenous breeds in areas where there are serious problems with parasite burdens, but only with regular – and often high levels – of anthelmintics – a strategy that most resource-poor farmers cannon sustain.

In arid and semi-arid regions such as Somalia the Sahel and Arabia, the envelope of livelihood options both for people and for animals is highly restricted and thus physical and behavioral adaptations to the environment are required. But as mentioned, our Western, industrially based and high technology-input lifestyles, whether for people or for livestock, tend to obscure this critical interface. The map of Somalia, second below, shows just how few options – other than marginal pastoralism – are available to Somali inhabitants:

Close up of Somalia and its resources:

Blue = food crops (sorghum, vegetables, grazing)

Orange= sugar cane

Pink = cotton

Brown = pastoral – most of the country

To supplement these meager resources, pre-modern trade from the interior of Africa to Somalia and the Indian Ocean coast consisted of gums, ivory, slaves, and other minor products. From the coast, sea trade moved the produce across the Indian ocean and to the Middle East. These traditional commodities of trade have ceased.

Caravan with slaves carrying ivory, moving towards the Somali coast. Notice that the sheep on the lower right appears to be a fat-tailed sheep Source: Speke, What Led to the Discovery of the Nile

In modern times, and with the collapse of this trade and of the Somali state and economy, sea piracy has become one – though certainly not the only way – of supplementing pastoralism:

Just the last couple of weeks, kidnapping of humanitarian assistant staff has become the ‘new way’ to gain quick cash (article below).

Related articles

- How feud wrecked the reputation of explorer who discovered Nile’s source (guardian.co.uk)

- Cuisines and Crops of Africa, 19th Century – Zambezi River Watershed in Southern Africa (dianabuja.wordpress.com)

- Eating in the Horn of Africa: camel, goat and. . .spaghetti? (gadling.com)

- 30 000 kids dead in 3 months (jbaynews.com)

- Somalia has best chance for peace in years: UN envoy (laaska.wordpress.com)

- Gunmen kidnap Spanish doctors near Kenya-Somali border – BBC News (news.google.com)

- Cuisines and Crops of Africa, 19th Century – The Limits of Pastoralism as a Lifestyle (dianabuja.wordpress.com)

- New Somalia infighting could escalate humanitarian crisis in horn of Africa region (ronaldbera.wordpress.com)

- Horn of Africa:Kenya seeks UN audience as Eriterian envoy blames Ethiopia for diplomatic row (laaska.wordpress.com)

- U.S. Response to Humanitarian Crisis in the Horn of Africa (appablog.wordpress.com)

- Piracy ‘delaying vital food aid from reaching Somalia’ (cnn.com)

- USAID: Horn of Africa drought fact sheet – Fiscal Year 2012 (danielberhane.wordpress.com)

- Somalia: Western Media Indulge US and French Denials of New War in Famine-Hit Horn of Africa by Finian Cunningham (dandelionsalad.wordpress.com)

- Somalis returned to famine areas (bbc.co.uk)

Pingback: Sahelian City-States in the Western Sahel: Part 2 | DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, The Middle East, Agriculture, History and Culture

Pingback: domestic violence against men

Pingback: Website

Pingback: Life and Livestock in the Arid Areas of Somiland, 1850′s « Dianabuja's Blog

Pingback: 2010 in review – blog vital statistics from Wordpress « Dianabuja's Blog

Pingback: Most Popular Blog Pages – Why?! « Dianabuja's Blog

They placed the fat in a pot and simmered it over low heat for 4-5 hours, adding abundant salt.

LikeLike

Thanks for the info, Mariana. After the simmering, the meat would be cut in fine strips and air-dried? Or?

LikeLike

Fat tailed sheeps were bred by Pontiac Greeks (Northeastern Turkey). The fat-tail weight ranged from 10 to 13 kilos and was salted and stored in wooden barrels.

LikeLike

Mariana, that is interesting. Do you know how it was salted? I.e., sliced thin and sun-dried as here in Africa?

LikeLike

i never would have thought a tail could be so useful!

LikeLike

Maria – Fat-tailed, and fat-rumped sheep are common adaptations to arid and semi-arid climates, from Asia through North Africa – and down into South Africa. The fat of a sheep’s tail figures importantly into various cuisines, and I will blog more about that.

LikeLike