Scientific American has recently published the podcast Let Them Eat Dirt . This reminded me of a past blog I’d done on the topic and which I repost here:

“Dirt is matter out-of-place.” This quote, by the anthropologist Mary Douglas, points to the cultural relativity of the term ‘dirt’; of dirt being culturally defined. It is in reference to diseases that ‘dirt’ takes on a non-culturally and more universally defined aura. Hence, the eating of dirt – or geophagy – covers a wide range of both culturally and medically defined practices.

I don’t want to get into a discussion on the benefits or negative aspects of geophagy, but to bring to attention several examples that come from 19th Century Africa. This is in response to a series of hits onto my blog from the Wikipedia entry on ‘Geophagy’ – an entry that is being contested (geophagy seems to be an emotional topic!).

I cannot find where my blog is referenced in the Wiki entry, but in the spirit of contributing further information on the topic I offer the following, which points to the wide-spread practice of geophagy throughout Africa in the 19th Century and earlier – and the fact that causes for it may be multiple, from simple eating of ‘dirt’ through physiological or medicinal purposes.

Ant hill in Somalia. Here and elsewhere in Africa, ant hills are used as look-out towers and their soils may be eaten during times of famine - when it may be mixed with other food. Source: Royal Geographic Society

The following is from David Livingstone:

29th November, 1870.-Safura is the [local] name of the disease of clay or earth eating, at Zanzibar (coast of East Africa); it often affects slaves, and the clay is said to have a pleasant odour to the eaters, but it is not confined to slaves, nor do slaves eat in order to kill themselves; it is a diseased appetite, and rich men who have plenty to eat are often subject to it.

The feet swell, flesh is lost, and the face looks haggard; the patient can scarcely walk for shortness of breath and weakness, and he continues eating till he dies.

Here many slaves are now diseased with safura; the clay built in walls is preferred, and Manyuema women when pregnant often eat it.

The cure is effected by drastic purges composed as follows: old vinegar of cocoa-trees is put into a large basin, and old slag red-hot cast into it, then “Moneyé,” asafoetida, half a rupee in weight, copperas, sulph. ditto: a small glass of this, fasting morning and evening, produces vomiting and purging of black dejections, this is continued for seven days; no meat is to be eaten, but only old rice or dura and water; a fowl in course of time: no fish, butter, eggs, or beef for two years on pain of death.

Mohamad’s father had skill in the cure, and the above is his prescription. Safura is thus a disease per se; it is common in Manyuema, and makes me in a measure content to wait for my medicines; from the description, inspissated bile seems to be the agent of blocking up the gall-duct and duodenum and the clay or earth may be nature trying to clear it away: the clay appears unchanged in the stools, and in large quantity.

A Banyamwezi carrier, who bore an enormous load of copper, is now by safura scarcely able to walk; he took it at Lualaba [a river, S.W. of Lake Tanganyika] where food is abundant, and he is contented with his lot.

Squeeze a finger-nail, and if no blood appears beneath it, safura is the cause of the bloodlessness.

FOOTNOTE:[by Horace Waller]

A precisely similar epidemic broke out at the settlement at Magomero, in which fifty-four of the slaves liberated by Dr. Livingstone and Bishop Mackenzie died.

This disease is by far the most fatal scourge the natives suffer from, not even excepting small-pox. It is common throughout Tropical Africa.

We believe that some important facts have recently been brought to light regarding it, and we can only trust sincerely that the true nature of the disorder will be known in time, so that it may be successfully treated: at present change of air and high feeding on a meat diet are the best remedies we know.-ED.

Above from: The Last Journals of David Livingstone, in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death, Volume II (of 2), 1869-1873 Continued By A Narrative Of His Last Moments And Sufferings, Obtained From His Faithful Servants Chuma And Susi

– Editor: Horace Waller

The following examples are from a book on the topic of Geophagy by Berthold Laufer:

T. F. Ehrmann (Geschichte der merkwiirdigsten Reisen, VII, 1793, p. 70; after J. Matthew’s Journey to Sierra Leone 1785-87) speaks of a white, soap-like earth found here and there in Sierra Leone and so fat that the Negroes frequently eat it with rice, because it melts like butter; it is also used for white-washing their houses. Ehrmann adds, “A curiosity which merits a closer investigation.”

The same clay was also reported by Golberry (1785-87) from Sene-gambia and described by him as a white, soap-like earth as soft as butter and so fat that the Negroes add it to their rice and other foods which thus become very savory. This clay is said not to injure the stomach (Lasch, p. 216).

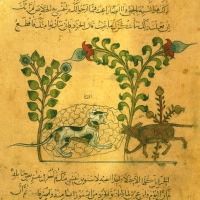

Gaud (Les Mandja, p. 151, Brussels, 1911) writes, “At the present time it is only during famines that the Mandja (in the French Congo) gather the earth of termites’-nests and consume it mixed with water and powdered tree-bark. This compound is said to assuage the tortures of hunger in a singular manner. We think that this effect must be attributed not only to the physical action resulting from the filling of the stomach, but also to the absorption of organic products existing in the clay.

It is in fact known that the walls of the termites’-nests are built by the female workers with tiny clay balls kneaded by them by means of their saliva. It would not be surprising that this saliva contains formic acid.”

R. F. Burton (Lake Regions of Central Africa, II, p. 28) writes that clay of ant-hills, called “sweet earth,” is commonly eaten on both coasts of Africa.

(Diana notes: I cannot find the reference to ‘sweet earth’ in Burton’s publication.)

Above from: GEOPHAGY – BY Berthold Laufer CURATOR, DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY CHICAGO, U. S. A. 1930

-3.233595

29.159775

Red peppers and garlic being boiled at the Hotel club lac Tanganyika, to make pepper sauce

Red peppers and garlic being boiled at the Hotel club lac Tanganyika, to make pepper sauce

![Baking Holy Bread in the Coptic Monasteries of the Eastern Desert of Egypt [qurban; 'urban]](https://i0.wp.com/dianabuja.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/one-whittemore_s-expedition-before-leaving-the-monastery-of-saint-anthony-egypt-1930-19312.png?resize=200%2C200&ssl=1)